Why I Keep Returning to the Classics

- moodmagex

- Dec 16, 2025

- 3 min read

I don’t return to the classics because they are revered.

I return because they are honest; often painfully so.

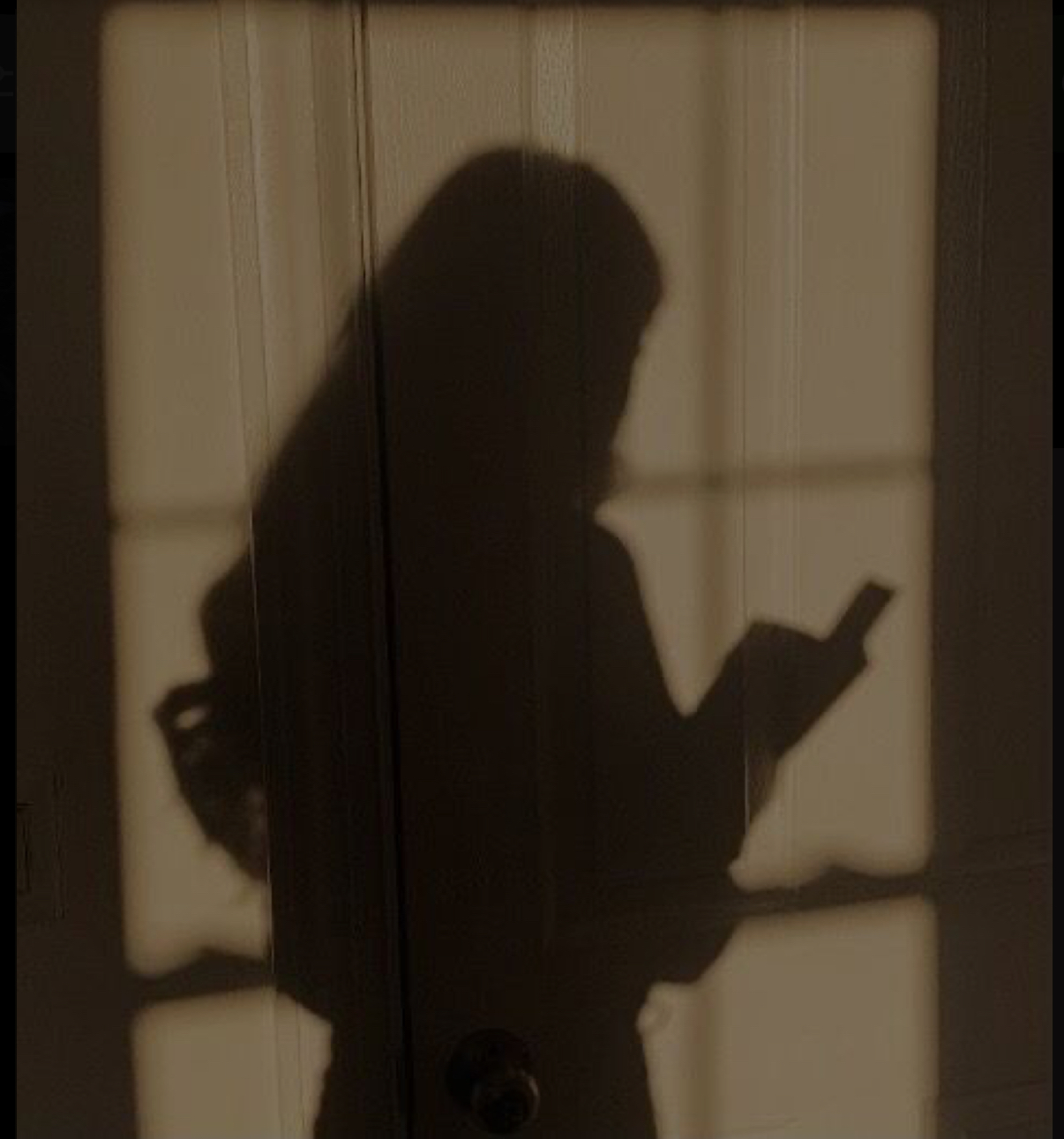

There is a particular quiet to these books. Worn spines. Sentences that do not hurry. Words that seem to breathe. Reading a classic feels less like consumption and more like communion, as though the book is asking not how fast you can read it, but how much of yourself you are willing to bring.

The classics do not flinch from discomfort. Dostoevsky opens Crime and Punishment with a man already unwell in his soul, and refuses to look away. Guilt presses in until it becomes unbearable, until conscience itself feels like a kind of fever. “Pain and suffering are always inevitable for a large intelligence and a deep heart,” he writes, and the truth of it settles slowly, heavily, like something long known but rarely said aloud.

Camus, in The Stranger, offers a different kind of unease. A narrator stripped of expected emotion, refusing grief as performance. “I opened myself to the gentle indifference of the world,” Meursault tells us, and suddenly the book is no longer about him, it is about us, and our need for meaning, for reaction, for proof that someone feels the way we think they should.

What keeps me returning is how these stories allow people to be incomplete. In Jane Eyre, love is not enough if it costs the self. “I am no bird; and no net ensnares me,” Jane insists, choosing autonomy over devotion. And in Pride and Prejudice, beneath the wit and romance, Austen quietly dismantles pride and prejudice alike, reminding us how often we misunderstand one another before we ever truly see.

The language in the classics asks for reverence, not because it is ornate, but because it is deliberate. Virginia Woolf turns an ordinary day into something luminous in Mrs Dalloway, writing, “She had the perpetual sense… of being out, out, far out to sea and alone.” In one sentence, solitude becomes vast, elemental, inescapable. Kafka, on the other hand, compresses dread until it feels inescapable, writing in The Trial, “It’s often better to be in chains than to be free.” A sentence that tightens the chest even now.

What I love most is that these books change as we change. The first time I read Wuthering Heights, it felt wild and excessive, a storm of emotions with no restraint. Years later, it read like a warning. “Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same,” Catherine says, and suddenly the romance feels less romantic, more consuming, more dangerous. The story stayed the same. I did not.

There is comfort in their endurance. These books have been read in candlelight and lamplight, passed through generations of hands that felt loss, ambition, longing, and doubt just as we do now. “We are such stuff as dreams are made on,” Shakespeare reminds us, and the truth of it has not dimmed with time.

I don’t read classics because I think I should.

I read them because they meet me where I am.

They ask me to slow down. To sit with ambiguity. To accept that not everything is meant to be resolved neatly or kindly. The classics do not promise comfort, but they offer recognition. And sometimes, to be seen across centuries, through ink and paper, is the most sustaining thing of all.

Comments